“Todo lo que apremia

pronto habrá pasado;

pues sólo es capaz de consagrarnos

lo que permanece.”

Raine Maria Rilke (Soneto XXII)

Hay fotógrafos que te hacen detenerte y coger aire en un mundo donde lo auténtico escasea. Y es que vivimos una realidad repleta de simulaciones e imposturas, de intentos de gustar, de redes sociales, de premios por adecuarse a las últimas tendencias y lo que es peor de gente subida a un pedestal comprado para parecer más alta. Es agotador seguir ese ritmo, viendo cómo la endogamia lo devora todo en su intento por capitalizar el arte. Pero hay esperanza igual que hay horizonte, la clave está en saber ver “lo que en medio del infierno no es infierno, hacerlo durar y darle espacio”. 1

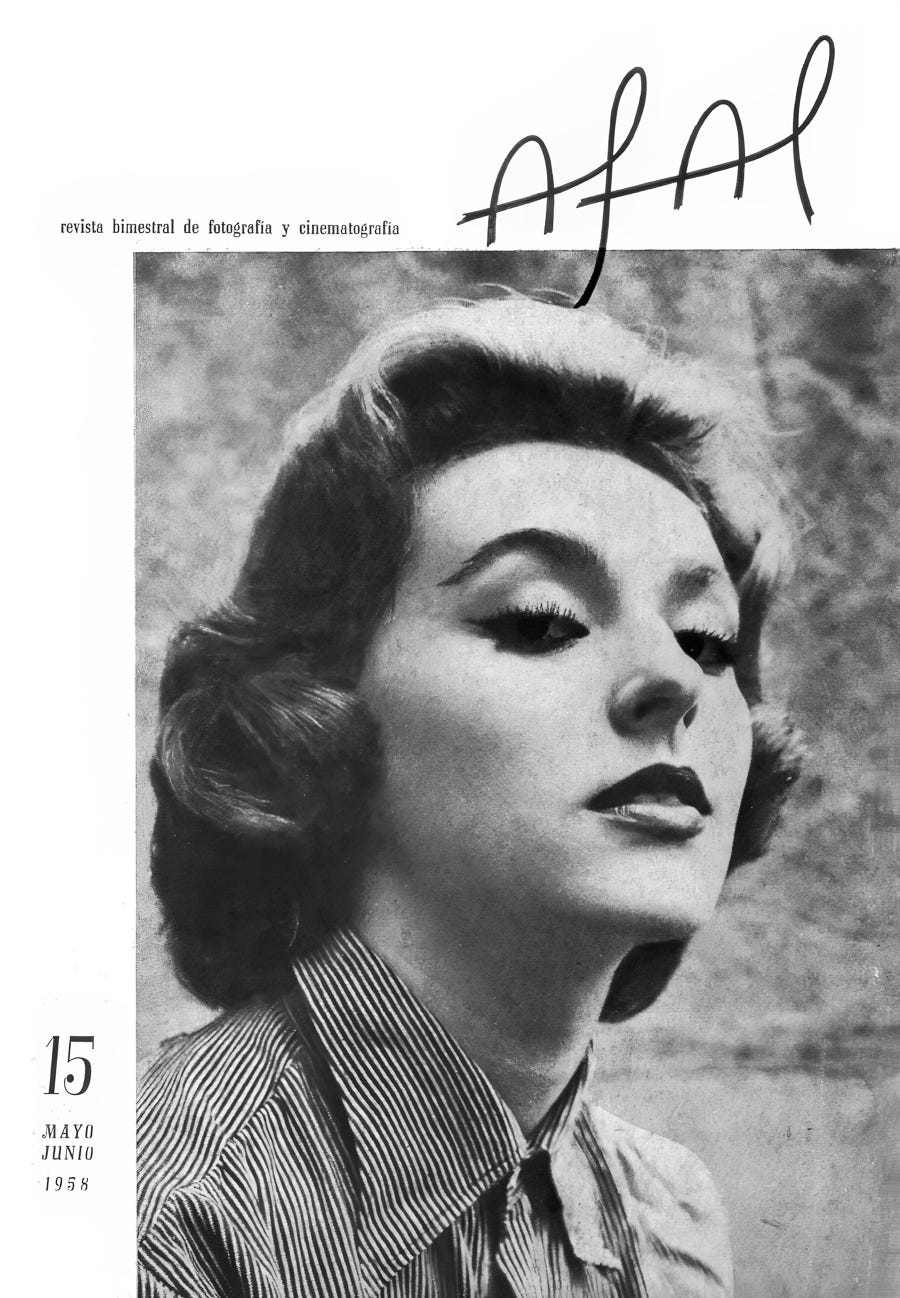

Somos presa de un inventario de nombres, habitamos un planeta de personas mayúsculas, de pensadores, escritores, artistas, teóricos, políticos, científicos, influencers y tertulianos hablando todos a la vez. Recordamos mezclando mensajes y por desgracia nos quedamos con poco de lo que realmente se hizo desde lo pequeño. Y así comienza esta historia, porque Afal, la revista que permitió un cambio de paradigma en la España de posguerra, es uno de los motivos por los que yo decidí involucrarme con la causa fotográfica. Así comencé a escuchar la voz de los fotógrafos a través de proyectos como La voz de la imagen o Detrás del instante y de ahí pasé a lo internacional con la magnífica serie Contacts. Mientras me preguntaba cuántos de ellos a lo largo del mundo, estaban siendo olvidados, decidí pasar a la acción.

Pronto tuve las cosas claras: quería crear algo que no existía, un archivo sonoro en el que conservar los pensamientos de los fotógrafos. Inspirada por muchos de los integrantes de Afal, cogí fuerzas para emprender un horizonte ambicioso. A todos ellos, les debo mi amor por la fotografía española, que creció desde mi posición profana y curiosa.

Hace tres años tomé la firme decisión de recordar cada día lo valioso de la obra y dar su lugar en la memoria colectiva a todos los que han hecho y hacen algo significativo al ponerse detrás de la cámara. Algún día, este archivo que es ahora Audioteca Fotográfica, será un legado que nos permitirá recordar nuestro mundo y las ideas e historias ligadas a las imágenes. Porque esto para mí no es un entretenimiento sino un camino que abrir en favor de lo que nos hacen humanos.

“All that presses us

will soon be gone;

for only what endures

has the power to consecrate us.”

– Rainer Maria Rilke (Sonnet XXII)Some photographers make you stop and catch your breath in a world where authenticity is scarce. We live in a reality filled with simulations and pretence, with attempts to please, social media antics, the reward for adhering to the latest trends and, worst of all, people standing on pedestals they bought to appear taller. Keeping up with this pace is exhausting, watching how nepotism devours everything in its attempt to capitalise on art. But there is hope, just as there is a horizon. The key lies in learning to see “what, amidst the hell, is not hell, making it last and giving it space.”

We are captives of an inventory of names, inhabiting a planet of capital-letter people – thinkers, writers, artists, theorists, politicians, scientists, influencers, and pundits, all speaking at once. We remember by blending messages, and unfortunately, we retain little of what was truly accomplished through small, humble efforts. And this is where this story begins, because Afal, the magazine that enabled a paradigm shift in post-war Spain, is one of the reasons why I chose to involve myself in the cause of photography. This is how I began to listen to the voice of photographers through projects such as La Voz de la imagen or Detrás del instante, and from there, I ventured onto the international stage with the magnificent series Contacts. As I wondered how many of them, across the world, were being forgotten, I decided to take action.

It soon became clear to me: I wanted to create something that didn’t yet exist – a sound archive to preserve photographers’ thoughts. Inspired by many of Afal’s members, I found the strength to embark on an ambitious journey. To all of them, I owe my love for Spanish photography, which grew from my once-innocent and curious perspective.

Three years ago, I made the firm decision to honour the value of their work each day and to ensure that those who have made and continue to make a significant impact by standing behind the camera are remembered in our collective memory. One day, this archive, now called the Audioteca Fotográfica, will become a legacy that allows us to recall our world and the ideas and stories tied to images. Because for me, this is not entertainment but a path to carve in favour of what makes us human.

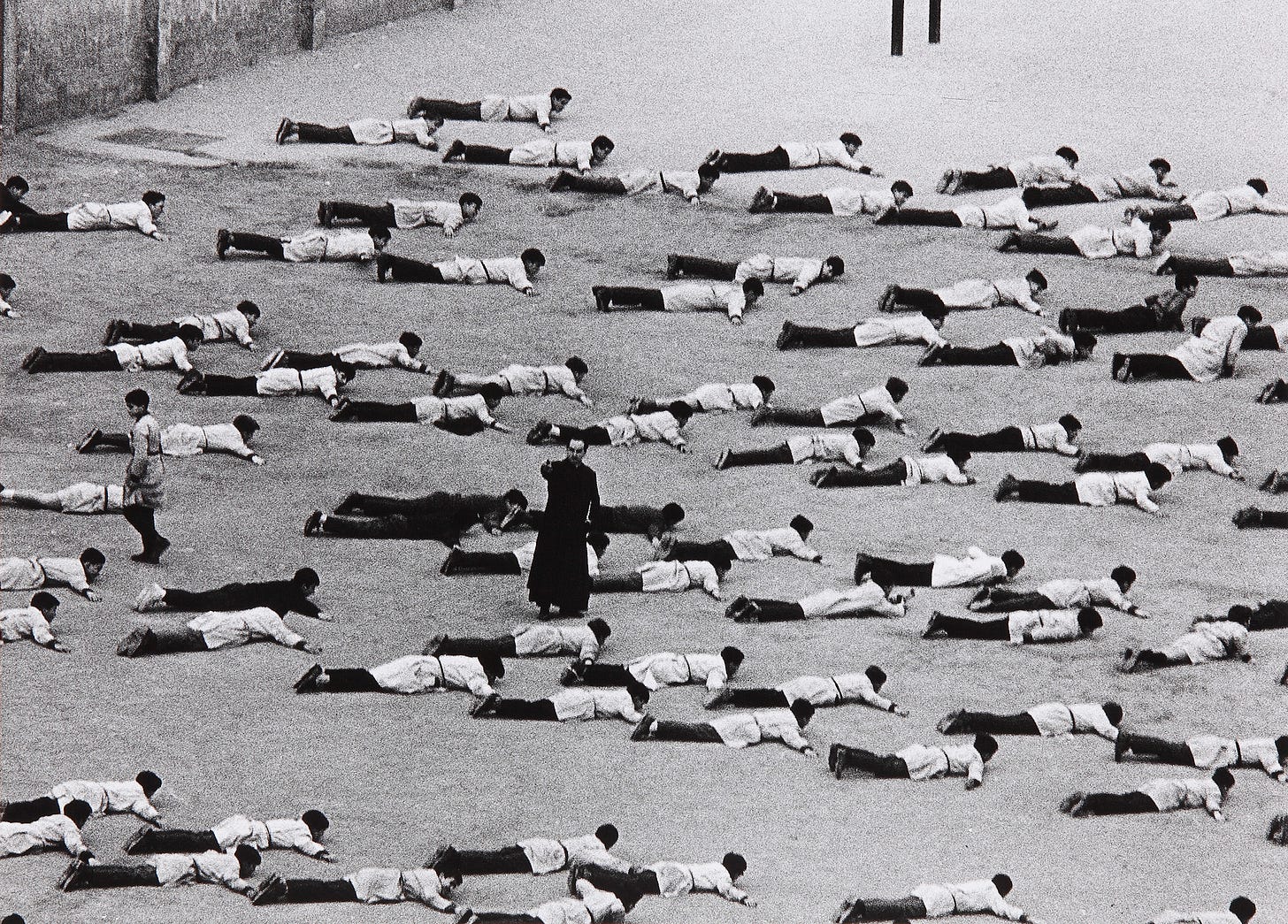

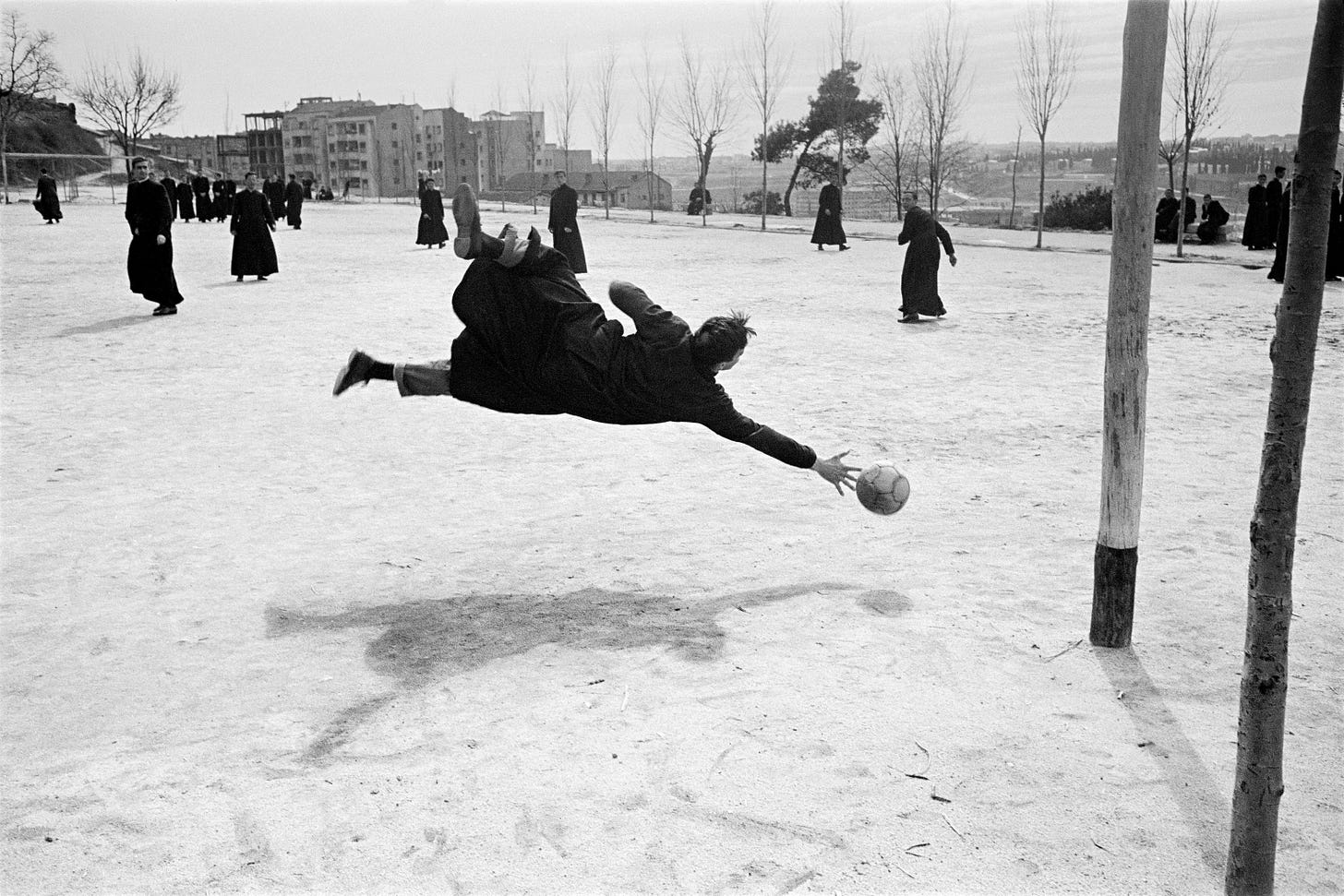

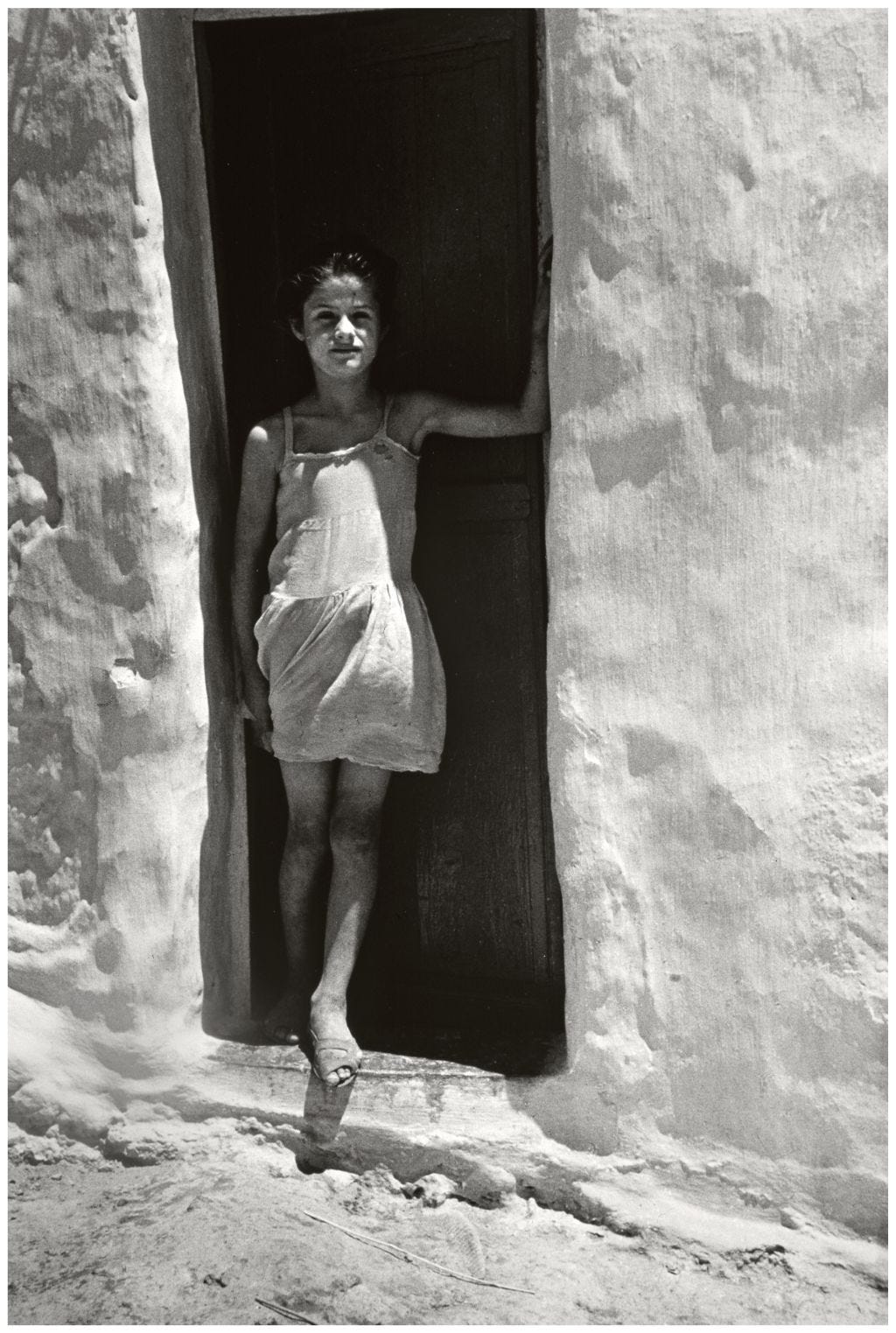

Por eso quiero nombrar a aquellos que han retratado con honestidad la verdad de su tiempo, personas que a través de su mirada nos ayudan a comprender una España de posguerra que se revela y se abre tanto en su herida como en su evolución. Estos fotógrafos merecen no ser solo parte de una exposición sino parte de vuestra memoria.

Joan Colom, Gabriel Cualladó, Francisco Gómez, Gonzalo Juanes, Ramón Masats, Oriol Maspons, Xavier Miserachs, Francisco Ontañón, Carlos Pérez Siquier, Leopoldo Pomés, Alberto Schommer, Ricard Terré, Julio Ubiña

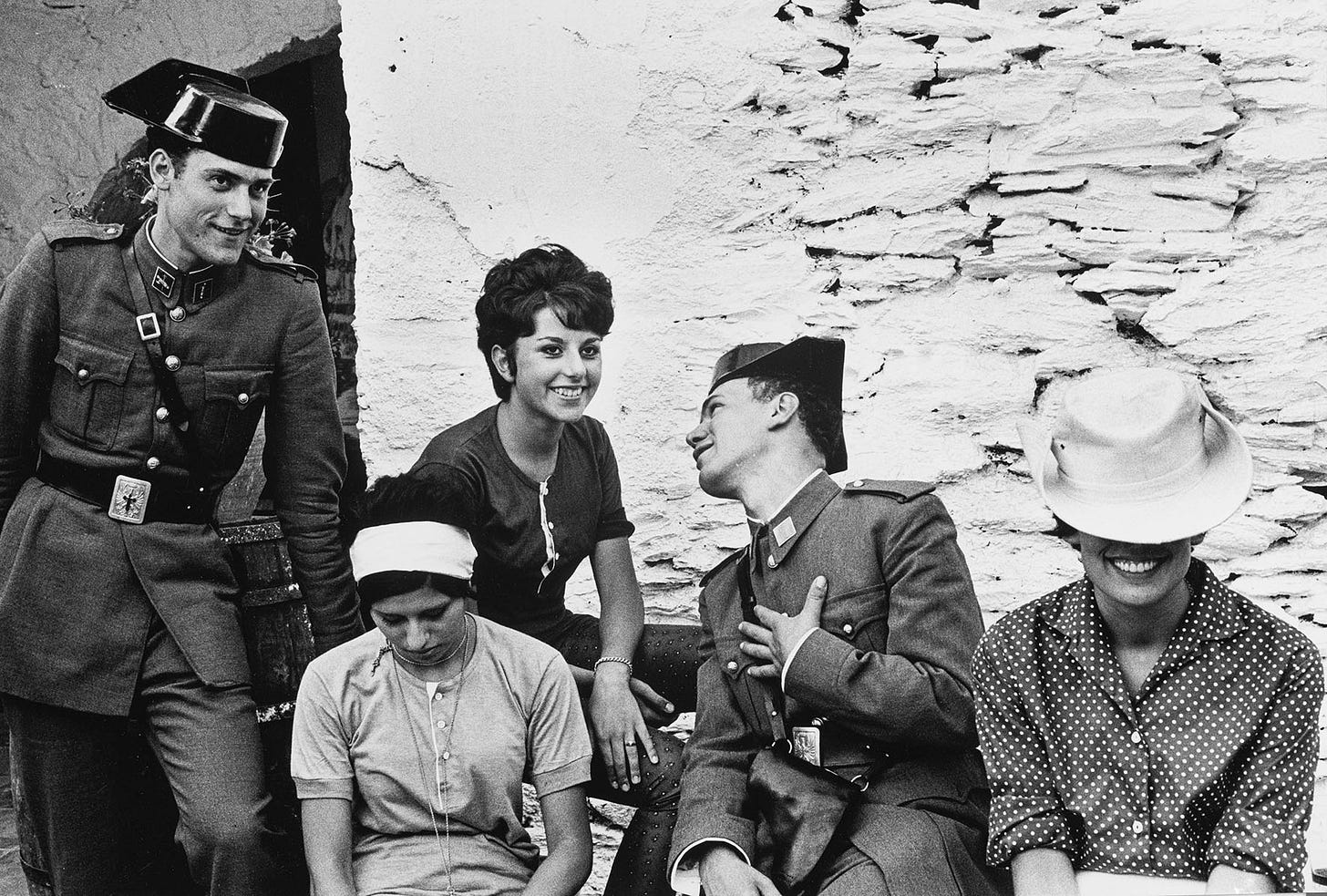

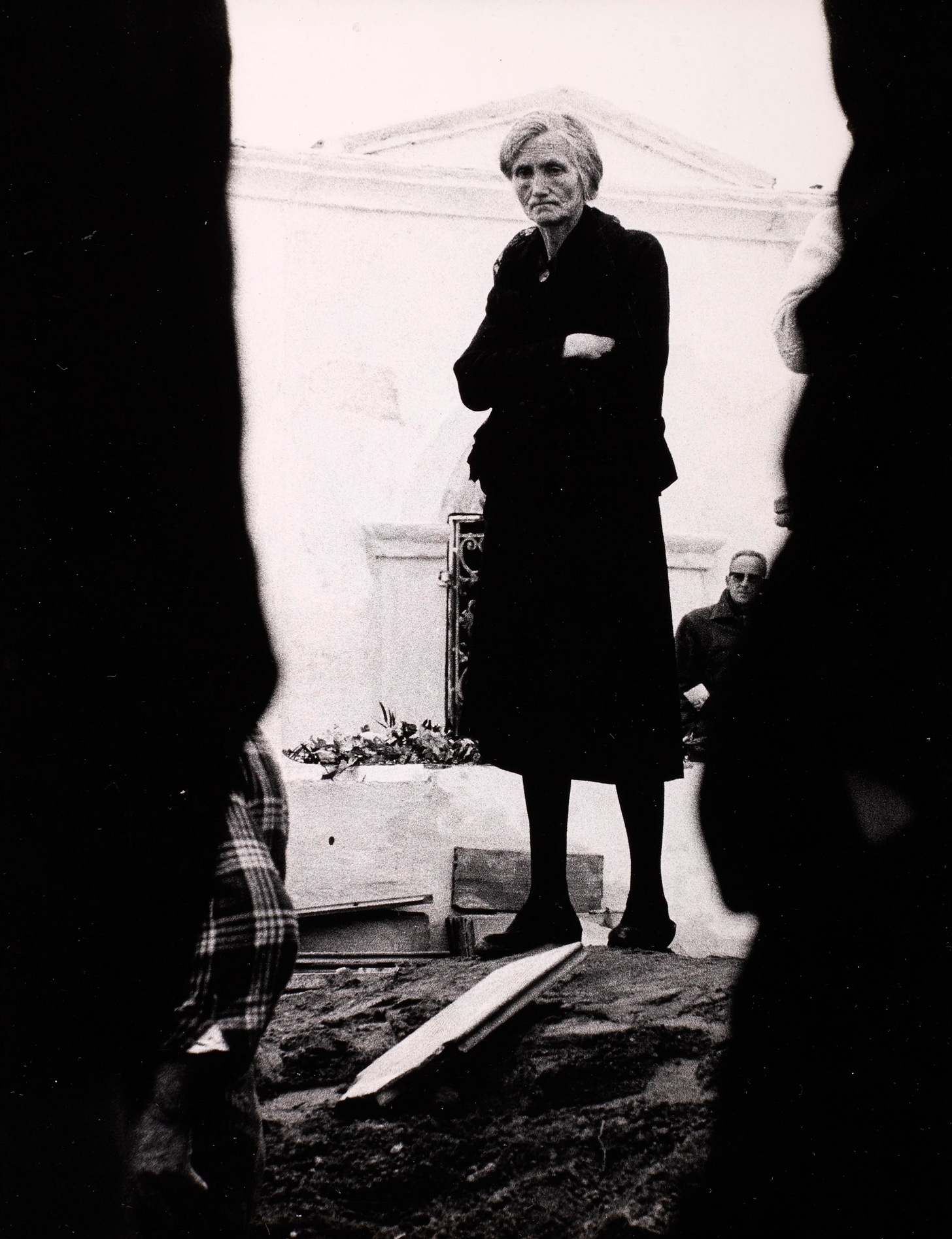

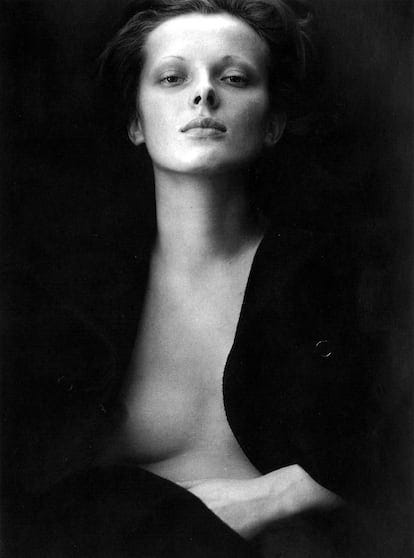

Este rosario de nombres no es solo un listado de talentos; es un mapa de complicidades. Ellos crearon puentes donde parecía haber muros, generaron diálogos y búsquedas desde la autodeterminación y la apertura colaborativa. No olvidemos que, en la España de los años 50 y 60, los espacios para el arte eran escasos y, a menudo, vigilados. La revista AFAL no fue simplemente un medio, sino un refugio, una luz en la oscuridad.

This is why I want to name those who have honestly captured the truth of their time, individuals who, through their gaze, help us understand a post-war Spain that reveals itself in its wounds as well as its evolution. These photographers deserve to be not just part of an exhibition but part of your memory:

Joan Colom, Gabriel Cualladó, Francisco Gómez, Gonzalo Juanes, Ramón Masats, Oriol Maspons, Xavier Miserachs, Francisco Ontañón, Carlos Pérez Siquier, Leopoldo Pomés, Alberto Schommer, Ricard Terré, Julio Ubiña

This list of names is not merely a roster of talent; it is a map of complicity. They built bridges where walls once stood, creating dialogues and searches driven by self-determination and collaborative openness. Let us not forget that, in 1950s and 60s Spain, spaces for art were scarce and often under surveillance. The magazine AFAL was not simply a medium; it was a refuge, a light in the darkness.

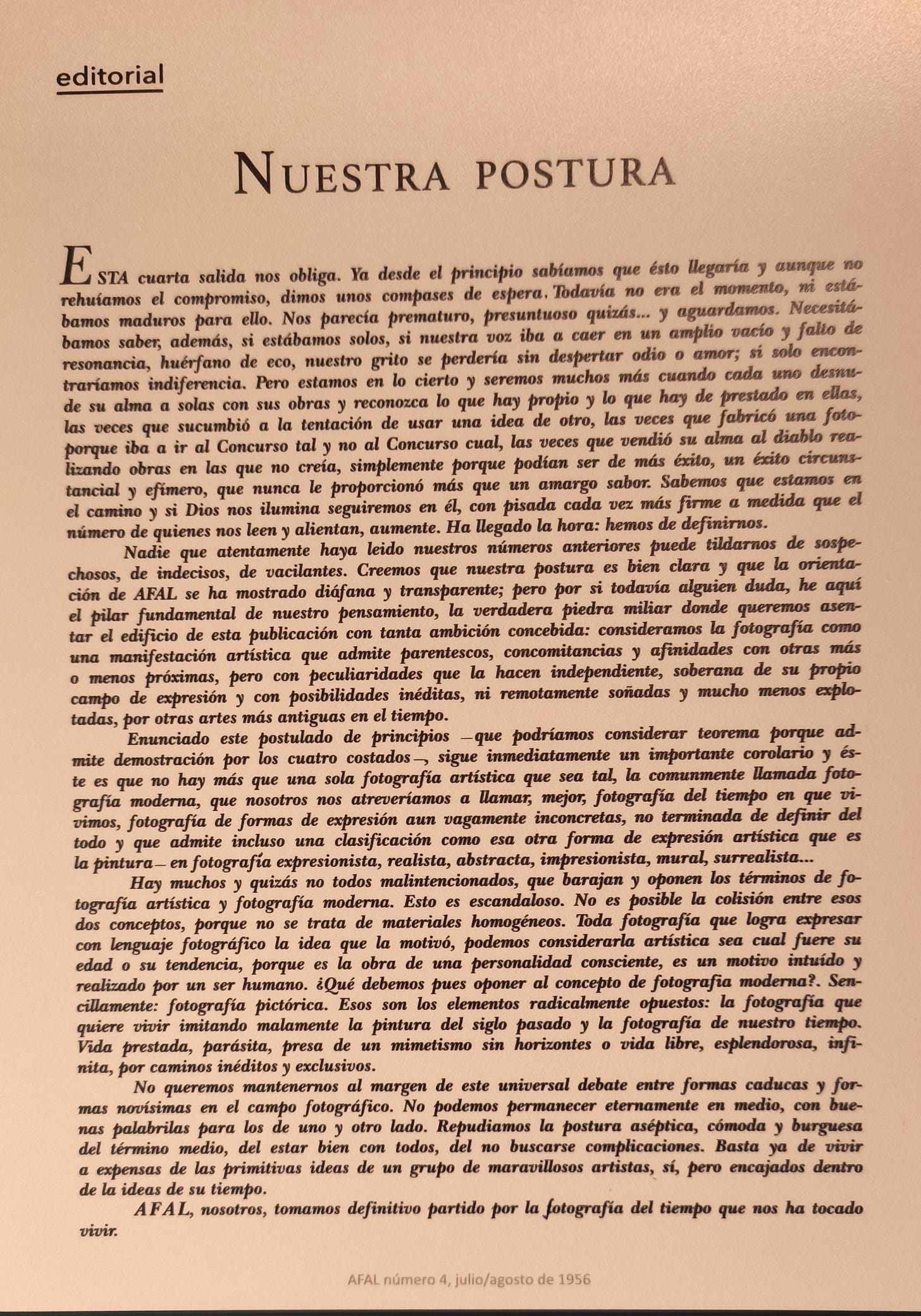

Afal representó un cambio de paradigma. En sus páginas, lo cotidiano se volvía extraordinario, las imágenes no eran un escaparate decorativo, sino una herramienta para mirar la verdad de frente. En un contexto de censura y represión, sus fundadores, José María Artero y Carlos Pérez Siquier, lograron lo que parecía imposible: un espacio donde el arte y la realidad convivieran, libre de artificios y siendo capaces de romper las narrativas dominantes. Era una ventana abierta a una España que empezaba a reconocer sus heridas, pero también a vislumbrar su evolución.

Afal es el recordatorio de que el arte no se hace para gustar, sino para resistir y cuestionar. En cada número de la revista, en cada fotografía publicada, había una declaración de intenciones: capturar la esencia de lo real y compartirla con quien estuviera dispuesto a mirar.

«En palabras de la comisaria del proyecto, Laura Terré, Afal fue mucho más que una revista de fotografía; fue una plataforma que unió a jóvenes fotógrafos en un espacio independiente, con un espíritu revolucionario que los marcó para siempre. Como afirmó Xavier Miserachs en 1998, “AFAL – y nosotros no lo sabíamos – era el internet de la época”. Su independencia económica y su resistencia a las presiones comerciales le permitieron mantener un carácter único que atrajo a los fotógrafos más innovadores de la época. Sin financiación de casas comerciales y con un esfuerzo de trabajo incansable de sus fundadores, Afal se convirtió en el motor de la renovación de la fotografía española en los años 50»2

Ciertas exposiciones están llenas de voces, por eso cuando uno camina por sus salas se encuentra prestando atención también al sonido que proviene del espacio. Así, el diseño expositivo cuando está bien hecho, genera un espacio para el diálogo. Y eso es algo que tenemos que agradecer a personas como Pascual + Vincent, porque saber contextualizar los pequeños detalles genera un ambiente propicio para que la historia pueda ser no sólo escuchada, sino recordada.

Afal represented a paradigm shift. In its pages, the ordinary became extraordinary; the images were not a decorative showcase but a tool for confronting the truth head-on. In a context of censorship and repression, its founders, José María Artero and Carlos Pérez Siquier, achieved what seemed impossible: a space where art and reality coexisted, free of artifices and capable of challenging dominant narratives. It was an open window into a Spain that was beginning to acknowledge its wounds while also glimpsing its evolution.

Afal is a reminder that art is not created to please but to resist and question. In every issue of the magazine, in every photograph published, there was a declaration of intent: to capture the essence of the real and share it with anyone willing to look.

“In the words of the project’s curator, Laura Terré, Afal was much more than a photography magazine; it was a platform that brought young photographers together in an independent space, with a revolutionary spirit that shaped them forever. As Xavier Miserachs said in 1998, ‘AFAL – and we didn’t know it – was the internet of its time.’ Its financial independence and resistance to commercial pressures allowed it to maintain a unique character that attracted the most innovative photographers of the era. Without funding from commercial houses and through the tireless efforts of its founders, Afal became the driving force behind the renewal of Spanish photography in the 1950s.”

Certain exhibitions are full of voices, which is why, as you walk through their rooms, you find yourself listening to the sound of the space itself. A well-executed exhibition design creates room for dialogue. This is something we owe to people like Pascual +Vincent, as their ability to contextualise the smallest details creates an environment where history can not only be heard but remembered.

«La exposición "Revista Afal, pequeña y libre" se centra en los 36 números publicados de la revista Afal (1956-1963), más tres boletines adicionales. El objetivo principal es resaltar la narrativa de la revista misma, sus vicisitudes, anécdotas y valores, alejándose de enfoques previos que se han centrado en los fotógrafos que participaron en ella. Este enfoque destaca temas como la censura, el humor, la poesía, el cine y el rol de las mujeres, complementando la narrativa visual con textos que refuerzan la accesibilidad para todos los públicos.

La intención era crear una exposición con más texto que fotografías, pero como en la revista, texto y fotografía debían ser complementarios: las imágenes ilustran el texto y el texto aclara las fotografías. Se emplea un diseño inspirado en la maquetación de la revista para crear una experiencia inmersiva que combine el respeto por el contenido histórico con un enfoque innovador y dinámico.»3

La exposición en la Serrería Belga no solo honra a los grandes nombres de Afal, como Pérez Siquier, Miserachs, Cualladó, Masats, Paco Gómez o Joan Colom, sino que también se adentra en las vicisitudes de la revista. Sus momentos de humor, los retos de la censura, las dificultades de impresión y la energía casi utópica de aquellos que se empeñaron en hacer posible cada número. En cada esquina de la sala, los textos y las imágenes dialogan, permitiéndonos ver no solo la obra, sino el esfuerzo, la pasión y el propósito detrás de cada página.

Somos afortunados por poder disfrutar de un pasado tan bien contextualizado, por eso es importante correr la voz. Porque las buenas exposiciones, a veces ocurren desde lo pequeño para tocar el corazón de lo que somos.

“The exhibition Revista Afal, pequeña y libre focuses on the 36 issues of the magazine Afal (1956-1963), along with three additional bulletins. The primary aim is to highlight the narrative of the magazine itself – its vicissitudes, anecdotes, and values – steering away from previous approaches that have focused on the photographers who participated in it. This perspective emphasises themes such as censorship, humour, poetry, cinema, and the role of women, complementing the visual narrative with texts that enhance accessibility for all audiences.

The intention was to create an exhibition with more text than photographs, but, as in the magazine, text and photography were to complement each other: the images illustrate the text, and the text clarifies the photographs. The design, inspired by the magazine’s layout, seeks to create an immersive experience that respects the historical content while adopting an innovative and dynamic approach.”

The exhibition at the Serrería Belga not only honours the great names of Afal, such as Pérez Siquier, Miserachs, Cualladó, Masats, Paco Gómez, or Joan Colom, but it also delves into the inner workings of the magazine. Its moments of humour, the challenges of censorship, the difficulties of printing, and the almost utopian energy of those who endeavoured to make each issue possible. In every corner of the exhibition, texts and images engage in dialogue, allowing us to see not just the work but the effort, passion, and purpose behind every page.

We are fortunate to be able to enjoy a past so well contextualised, which is why it is important to spread the word. Because great exhibitions often emerge from something small, touching the very heart of who we are.

Pulsa el play para escuchar el texto en español.

Las Ciudades invisibles. Italo Calvino. Editorial Siruela.

Nota de prensa de la exposición Afal, pequeña y libre. Serrería Belga., Madrid.

Vincent Sáez + Pascual Martínez , responsables del diseño expositivo de Afal, pequeña y libre. Serrería Belga, Madrid.

Soy argentina y algunas de las imágenes que compartes las tengo en mi memoria por haberlas visto pasar en algún libro o vaya una a saber dónde exactamente. Cuánto poder el de la fotografía y cuánto espíritu estamos perdiendo. Me encanta tu proyecto.

Lo mejor de la fotografía de España.